This series of articles is intended to guide you through the program workflow that implements detection of watchtowers that Romans built along the frontier fortification called Limes Germanicus, also simply referred to as the Limes. The Limes separated the Roman Empire from the outer world. We will focus on the limes that stood between the Roman Empire and Germanic tribes in Central Europe around 2000 years ago. We could choose another structure or ruin as a subject to show how the detection works. However, for the sake of the topic – the detection, the watchtowers are a good enough example.

We will detect not the auxiliary forts, or the legionary fortresses, or camps, just the watchtowers. The purpose of the article series is to show how to use machine learning to detect any object of interest in the topographic, orthographic, and LIDAR maps.

I assume that the center of interest for any archaeologist are anthropogenic structures of an historical value. I have chosen to present the process of training the detection model specifically on LIDAR data, but adding orthophotography data to the mixture of available information is definitely a step in the right direction. You can see a full list of watchtowers in this document: LimesFührer.pdf.

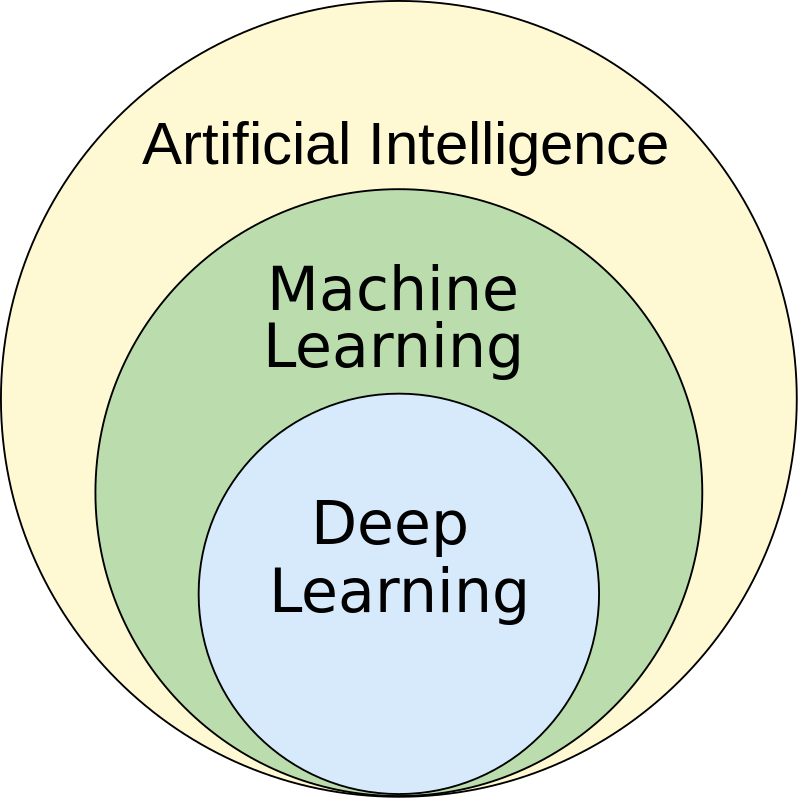

Machine learning or AI

Before we continue, I would like to say a few words about the terms AI, machine learning, detection, and classification.

We often hear the term AI used in different contexts. AI is a very broad term that encompasses the quest for of artificial intelligence – a human-like intelligence, or any intelligence that is better than ours. But that is not our goal here. I acknowledge that I am using the term AI in the name of the webpage. But we do not have to go that far, to implement a super intelligence, or an artificial general intelligence, to get help from computers. If true AI is ever implemented, it will be probably based on machine learning, or on a synthetic life, or on biological components. But here I would just stick to the term machine learning, and focus on solving problems using machine learning. Although machine learning doesn’t sound as cool as AI, it is a very useful tool for processing large amount of data. In archaeology, where multiple modalities are used to extract information about a site, machine learning is a valuable tool.

Machine learning is often an iterative process when – mostly a real-world – information is being compressed into a digital model using a consistent strategy that follows a convergent path to reach a minimum error. This part is called training. After the training, when the model is finished, we can feed the model with a new data, a vector of parameters, that are propagated through layers of decisions, which are defined by weights. The model can then be used to fulfill a highly specific task, e.g. detection of LIDAR structures.

To detect an object using machine learning, we have different methods and algorithms available. These algorithms are generally referred to as deep learning algorithms, producing deep learning models. Some of the most popular ones include YOLO, MaskRCNN, RetinaNet, Pyramid Scene Parsing, U-Net, Single Shot Detector, and more. In this series, I will focus on YOLO8 from Ultralytics and YOLO2 implemented by Apple.

It is always worth trying different deep learning methods on the same data to obtain an overview of the quality of the results. However, for the sake of simplicity, we will stick to one method in this series, which is YOLO.

Let’s now clarify the difference between detection and classification:

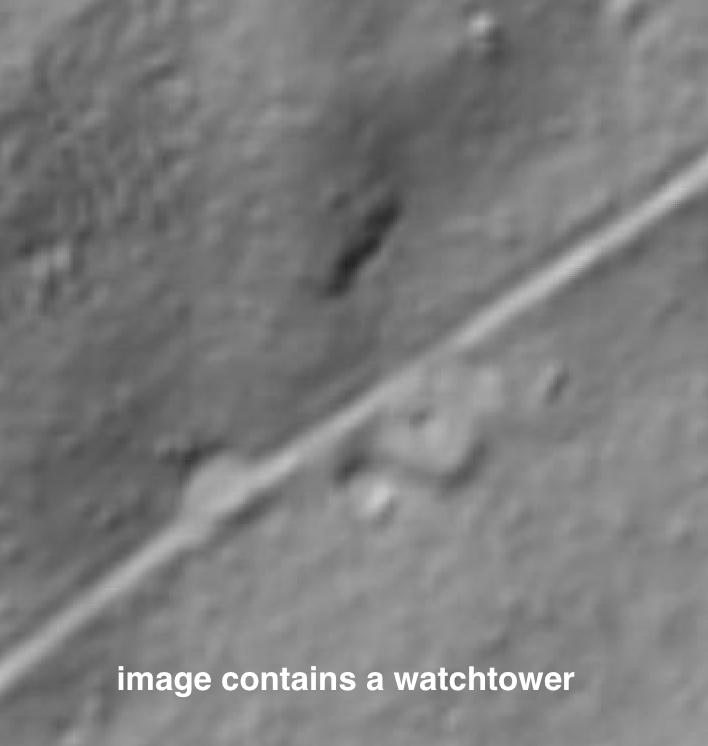

- Detection: a computer vision technique for locating instances of objects in images or videos.

- Classification: the ability of a deep learning algorithm to sort different types of data into different categories.

In the following images, you can see the difference between these two processes and their outcomes.

The subject of the following articles will be only detection, i.e., the result of our effort will be a detection that will tell us where the towers are located in the lidar background, and the output of the detection process will bound these towers within rectangles.

In the following text, I will refer to the more general term machine learning as it is often used in papers, and literature interchangeably with deep learning.

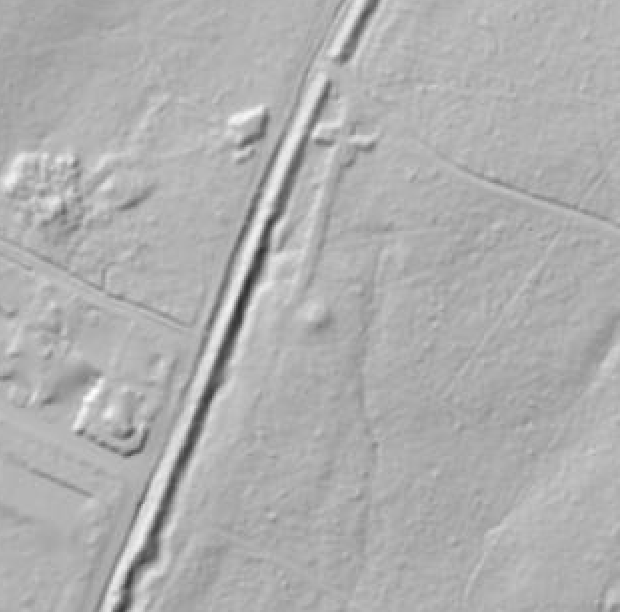

Training data

LiDAR technology provides a distinct advantage in detecting Roman watchtowers, especially in forest-covered areas. This is because LiDAR allows us to peer beneath the tree canopy, giving us access to the ground below – our primary area of interest. However, this method has its setbacks when applied to cultivated landscapes. The topographical nuances of such areas can be obscured by factors like plowing or erosion, especially in regions with unstable soil conditions. While there are alternative means for object detection such as aerial imagery, orthophotography (which is an aerial image adapted for mapping systems), magnetometry, and ground-penetrating radar, our research found that LiDAR sources showcased a significantly higher number of watchtowers compared to aerial images.

The model training will be as good as will be the number of available training data, therefore we will detect the watchtowers with a model trained on LIDAR data.

For effective object detection, a substantial amount of training samples is crucial. Unlike humans, machine learning lacks the innate adaptability to quickly recognize and generalize objects after only a few encounters. For instance, humans can identify a dog after seeing it a few times and confidently differentiate it from other animals, like tigers, in future encounters. While we can easily navigate challenges such as varying lighting or obscured views, like a dog partially hidden behind a bush, machine learning algorithms require more explicit and diverse data to achieve a similar level of flexibility.

Machine learning truly excels when provided with a plethora of training objects, especially in scenarios where the subjects are partially obscured, unclear, or have experienced distortion over time, such as a watchtower that’s been in ruins for 2000 years. The core message of these articles is to underscore this strength:

Allow machines to handle the vast array of edge cases in data generated by other machines. This leaves humans free to concentrate on tasks that require a higher degree of cognitive ability than what machines can currently provide.

And more data (with an expert)

Our journey into the world of machine learning in archaeology often revolves around two crucial parts: data collection and expert knowledge. For instance, there are detection models trained on thousands of images of cats and dogs against diverse backdrops. Here, the lines distinguishing cats from dogs are relatively straightforward, and we don’t always need a domain expert to make that differentiation.

However, the world of archaeology is a different playing field. Identifying archaeological sites requires a deep-seated expertise. This necessity not only complicates the data collection process but also makes it more expensive. It’s an inherent challenge in the field.

Another challenge lies in the limitations of archaeological data. Unlike the ever-growing population of cats and dogs, historical landmarks such as watchtowers don’t multiply over time. Once built, many have since become ruins or have undergone natural processes causing them to fade over time. This limitation extends to most archaeological sites.

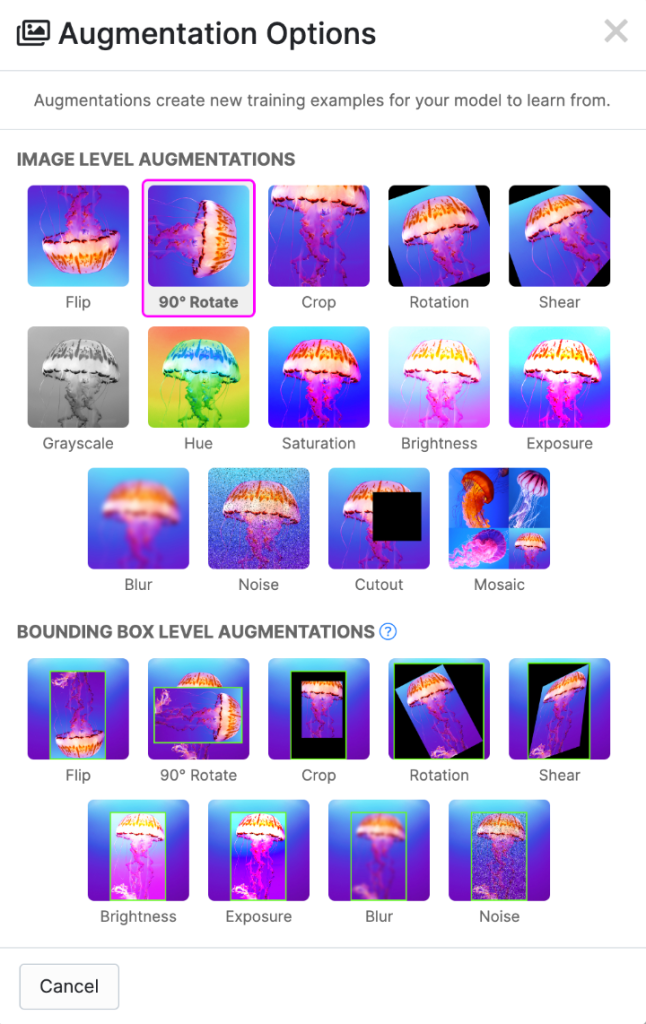

While tools exist that can synthesize training data, such as superimposing images of zebras onto different landscapes, these methods have their limits when applied to archaeologically significant objects. Techniques compensating for the paucity of training data will be important, a topic I’ll delve into in my subsequent article.

In archaeology, when applying machine learning, the following tasks prove to be the most challenging:

- Expert knowledge relevant to the specific problem: Archaeology encompasses various fields, and experts require significant time to develop a discerning eye in their specific area. If the individual creating the model lacks enough experience, many structures or sites might be mislabeled or misinterpreted.

- Transferability of the trained model across different geographies: While a particular culture might be responsible for the creation of a site or structure, varying geological and climatic conditions can significantly impact the accuracy of a trained for environment A, but used in an environment B.

- Quantity of training data: As previously mentioned, the number of available sites is diminishing over time. This reduction is due to natural environmental factors, urbanization, and regrettably, vandalism.

- Resolution of the training data: That is related to the point 3. If the final product using the trained model should be versatile, and robust enough with different data on the input, then it is necessary to sample the training data also with different resolution quality, that is, to use different zoom levels when making the data snapshots.

In general it is very useful to collect as many data as possible.

When there are not enough data, we can tackle this problem from different perspectives:

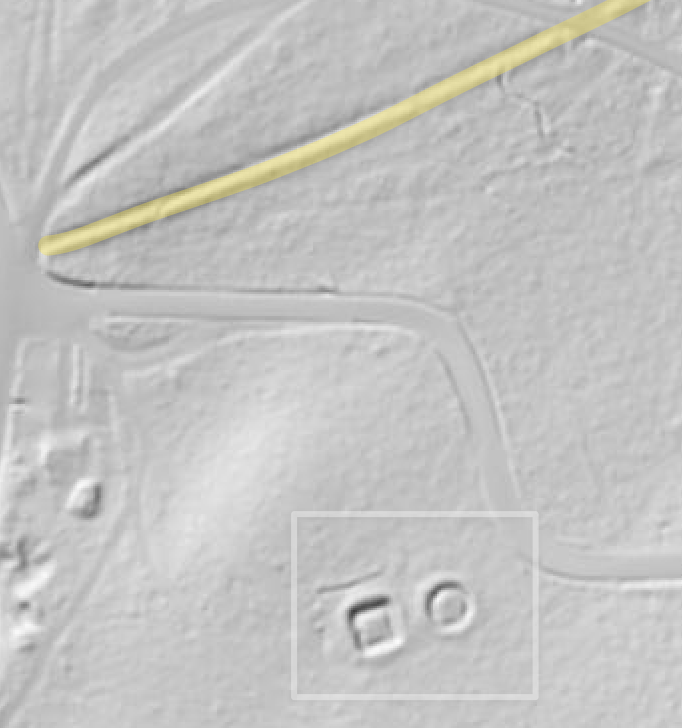

- Accepting false positives: It is better to detect more objects than necessary ( false positives) then to miss them (false negatives). We can integrate similar data in the training phase by adding another class of objects to the model. E.g. in this article I have collected samples of images of the Roman watchtowers along the Limes. But there are recurring very similar structures in the LIDAR: mounds. It can be very tricky to train the model also for another class that is similar to the object in the focus. But in the end it is a help anyway, and researcher (or another classification layer) can later review all detected object, either immediately, or, in case of the researcher, by visiting the location and exclude false positives.

- Creating synthesized data: We can isolate some samples and merge them into various environments using image tools. This way we can generate many more samples and use them in the training phase. But as I have mentioned above, in case archeological sites, the tasks is way more difficult as the archeological sites disintegrate under quiet specific conditions. I would assume a 3D physic engine would be needed to generated different eroding stages of the site, and its results could be used later for the synthesis.

- Reusing a pre-trained models: In some cases using pre-trained, already existing, models can improve performance of your model. There can be useful patterns in the pretrained model, that can be translated to your new model. This case needs to be tested, as it is hard to predict the impact on the performance of your model.

- Training samples augmentation: It is very useful to augment your training samples with different image transformation, either in terms of color, composition, or size. Images can be also merged together. Many tools support this functionality with different control arguments: rotation, translation, brightness, etc.

- Different semantic resolutions: Instead of focusing on the sites as complete objects, we can focus on few features that are specific and unique to that site. E.g. if we want to train a model to detect Roman camps, we do not need to sample only complete camps, but we can make many more samples from the individual camps: e.g. from their fortifications. From a single camp, we could get ten more samples along the camp’s wall. Then I can imagine, we could use the detected objects – part of walls – as inputs for another algorithm like the graph neural networks to reproduce a concave properties of the camps.

Accepting false positives: In the images above we can see that the mounds on the left are similar to the ruined base of the watchtower on the right. With this approach we will train the model also with the mounds, and that will help to avoid missing some watchtowers, that are similar to mounds. Source: windrossen.hessen.de.

Sources for the data

To gather adequate data for our project, I am using the LiDAR maps offered by Windrosen-Atlas Hessen – WindRAH and Bayern Atlas. Their LiDAR layers are quite similar, enabling me to trace the Limes from Hesse to its termination near the Danube river in Bayern. The more diverse our data sources, the better. Relying on a single map application could result in overtraining our model. Incorporating varied map applications enhances the diversity of our training data, bolstering the robustness of detection. Always ensure you have the right to use such data by checking copyright permissions specific to your project’s requirements.

To conclude, I’ve managed to gather 117 samples of watchtowers across Hesse and Bayern. Though not an ideal count for training, given that a subset is needed for testing, it’s a promising start. I am optimistic about garnering useful insights from this dataset.

In my next piece, I’ll explore the integration of expert knowledge, strategies for class designation, and the intricacies of the labeling process.

Leave a comment